Overview

This article explores how five influential thinkers —Confucius, Baruch Spinoza, Immanuel Kant, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Hannah Arendt— each highlight a core idea related to human autonomy, self-regulation, and the dangers of external coercion or unthinking conformity.

If I have seen further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants.

— Isaac Newton (1643 – 1727)

The Importance of Human Autonomy

These figures span ancient to modern philosophy, drawing from ethics, metaphysics, epistemology, language philosophy, and political theory. Collectively, their ideas emphasize empowering individuals to think, act, and govern themselves independently, rather than relying on divine, authoritarian, or systemic mandates.

This theme of individual agency ties their claims together: They all advocate for structures (ethical, rational, linguistic, or social) that foster self-directed behavior, warning against the perils of blind obedience or constrained thought. Their impacts on human society are profound, influencing everything from moral education and democratic governance to critiques of totalitarianism and modern analytic philosophy. However, their ideas also faced resistance, leading to personal and intellectual setbacks.

In analyzing each, I’ll provide an overview including their structural environments and how they shaped their method of thinking. I’ll also cover their societal impacts, methods of inquiry or dissemination, key setbacks, “annus mirabilis” (a “miracle year” of exceptional productivity, adapted from scientific contexts to philosophical breakthroughs), and how they might present their claims in a contemporary academic setting (e.g., conferences, journals, or interdisciplinary panels). I’ll draw on historical context, examples, nuances, and implications, including edge cases where their ideas have been misinterpreted or applied destructively. Finally, I’ll synthesize their common ties, overall societal impact, and suggest an appropriate hypothetical academic journal for their insights.

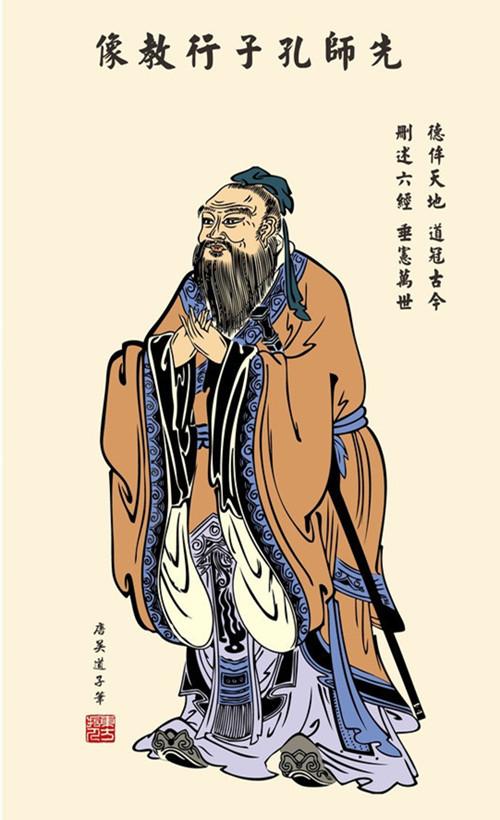

Confucius

(c. 551–479 BCE)

QUOTES

Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance.

The superior man understands what is right; the inferior man understands what will sell.

By nature, men are nearly alike; by practice, they get to be wide apart.

He who will not economize will have to agonize.

When we see men of a contrary character, we should turn inwards and examine ourselves.

EDUCATION

Education through the Six Arts and family ritual made moral learning a practice rather than abstract theory.

Confucius’s education was not institutional but cultural, ritual, and historical — shaped by the structures of Zhou society, political chaos of his era, and the weight of historical tradition.

1. Family and Tradition

Confucius was born into a once-noble family that had fallen into poverty. This meant early learning came through rituals, stories, and ancestral practices.

His mother, Yan Zhengzai, raised him in modest circumstances, emphasizing education, ritual propriety, and moral self-discipline despite limited means. This early exposure to both social marginality and traditional norms appears to have shaped Confucius’s lifelong concern with order, continuity, and self-cultivation.

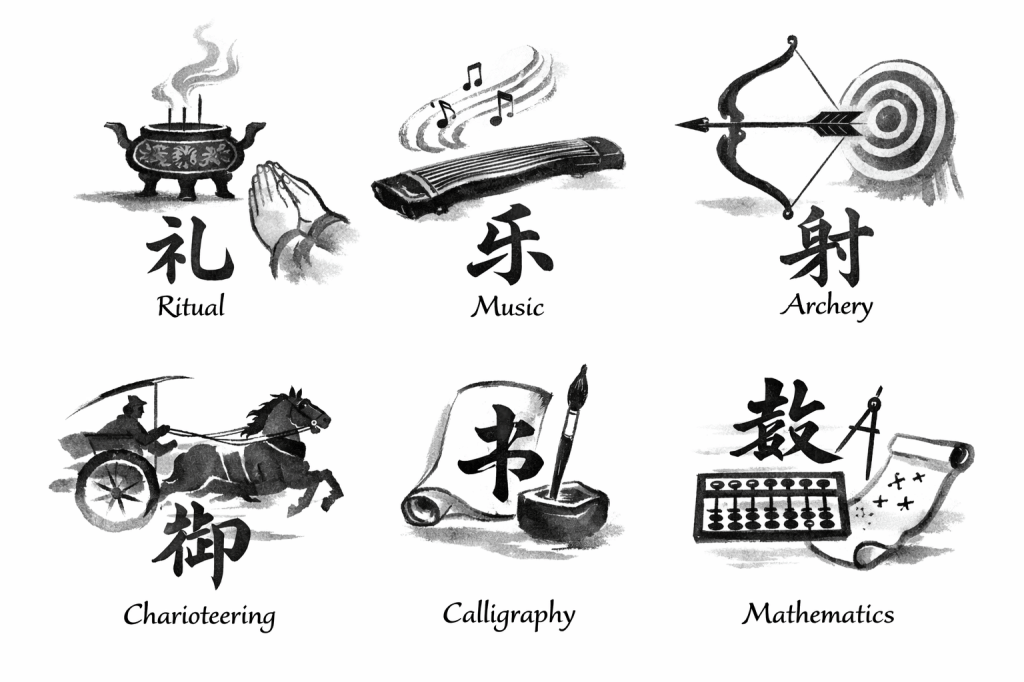

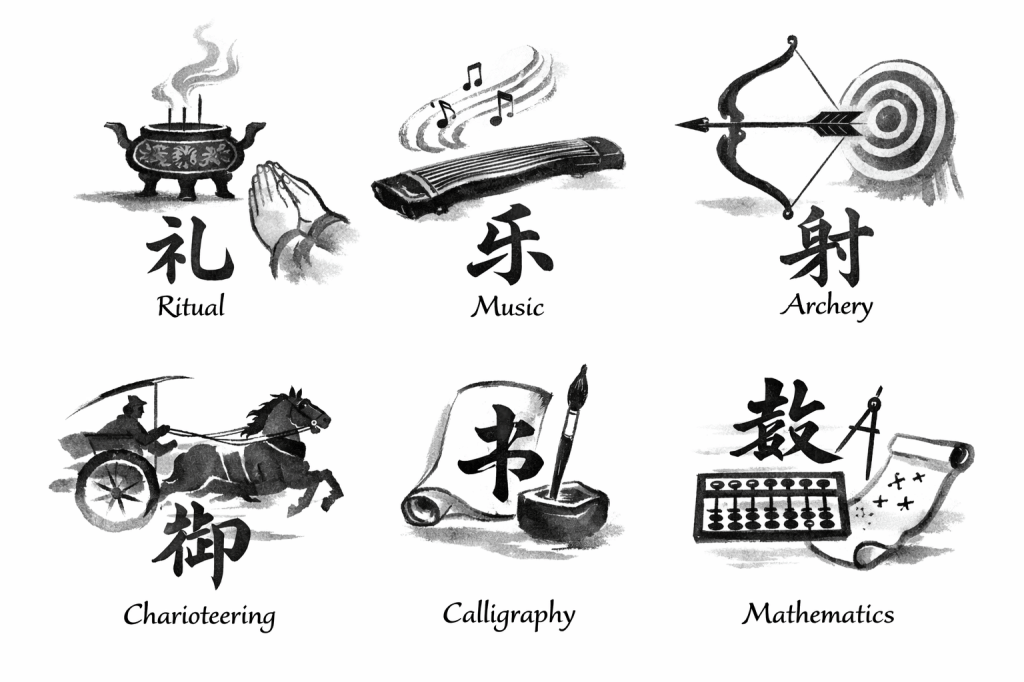

2. The Six Arts

In the Zhou world, “education” meant mastering the Six Arts (六艺, Liù Yì), an educational curriculum that aligned body, emotion, intellect, and ethics —a whole-person education.

These arts echo through later East Asian culture—martial arts, music pedagogy, calligraphy, even governance theory. Strip away the bronze vessels and chariots, and the underlying question still hums: What should a complete education actually cultivate?

| Art | Character | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ritual | 礼, Lǐ | Ritual was more than empty ceremony—ritual was social physics. It trained people to move through hierarchy, grief, joy, and power without tearing the fabric of the group. | Confucius saw lǐ as the external form of inner virtue. |

| Music | 乐, Yuè | Music shaped emotion and character. Proper music cultivated harmony; chaotic music signaled social decay. | Confucius famously judged governments by their music before their laws. Sound as moral technology. |

| Archery | 射, Shè | This wasn’t just about hitting a target. Archery trained posture, breath, focus, and humility. | In ritual archery contests, moral composure mattered more than accuracy—miss the target calmly, and you still passed. |

| Charioteering | 御, Yù | Driving a chariot required coordination, awareness, and trust. Symbolically, it trained leaders to “hold the reins” of themselves before attempting to guide others. | Power without self-control was considered dangerous. |

| Calligraphy | 书, Shū | Writing wasn’t neutral transcription. Calligraphy revealed the mind through the body. | Stroke order, pressure, and rhythm were read as windows into character—thought made visible. |

| Mathematics | 数, Shù | Math grounded philosophy in reality: land measurement, astronomy, calendars, logistics. | Pattern recognition in numbers mirrored the larger patterns of Heaven and Earth. |

Confucius’s Perspective

As a young man, Confucius received a broad classical education associated with the remnants of Zhou aristocratic culture, studying ritual, music, history, and administrative practices. Although not born into the ruling elite, he sought mastery of the cultural forms that had once structured political legitimacy. This outsider-insider position—trained in elite norms but excluded from hereditary power—became a defining feature of his intellectual trajectory.

3. Literature

Confucius saw himself as a “transmitter who invented nothing”. This tells us he was educated through:

- The Book of Songs

- The Book of Documents

- The Book of Rites

- The Spring and Autumn Annals

- The Book of Changes

This anchored him in historical precedent, training him to read texts as ethical guides. It also reinforces the idea that the past contains models for present action.

STRUCTURAL INFLUENCES

Confucius grew up in a single-parent household after his father died when he was three.

1. The Zhou Political Collapse

Confucius lived during a time of intense political fragmentation and moral decline.

Spinoza’s formal schooling took place in the all‑male Talmud-Torah school, founded in 1638. This school was run by adult male teachers, many of whom had been trained in Roman Catholic schools before fleeing Iberian persecution.

This instability shaped him by:

- Making him obsessed with restoring order

- Turning him toward ethical leadership as the solution

- Pushing him to articulate a vision of society grounded in virtue, not force

2. Ritual Culture of the Zhou Dynasty

The Zhou worldview held that ritual creates harmony, hierarchy is natural, and social roles are morally charged.

Confucius absorbed this deeply. It shaped his belief that:

- Ethics is relational, not individual

- Harmony is achieved through proper conduct

- Society is a network of roles, not isolated selves

3. Family Structure and Filial Piety

Confucius grew up in a single-parent household after his father died when he was three.

Impacts:

- Making the family the prototype for all social relationships

- Emphasizing filial piety as the root of virtue

- Viewing moral development as something nurtured through care, modeling, and respect

4. The Itinerant Teacher Tradition

Confucius was one of the first to make education broadly available.

These circles include:

- A culture where knowledge was transmitted through master-disciple relationships

- A belief that learning is lifelong

- A conviction that anyone with dedication could cultivate virtue

5. Textual Interpretation as Mode of Thought

These relationships exposed him to mechanistic physics, empirical science, and rationalist metaphysics.

- Interpreted inherited texts

- Treated them as moral guides

- Used them to critique contemporary society

6. The Social World of Scholars, Officials, and Ritualists

This dialogical, aphoristic setting grounded his philosophy in practical governance, reinforcing the idea that virtue is political.

Confucius gathered a circle of disciples from varied social backgrounds, advocating that moral education, rather than birth, should determine a person’s capacity for leadership. This stance quietly challenged entrenched aristocratic hierarchies while preserving respect for tradition.

Societal interactions with:

- Local rulers

- Ministers

- Ritual specialists

- Students who later compiled the Analects

STRUCTURAL ECOLOGY

Structurally, Confucius’s thought emerged from a convergence of personal loss, social instability, and historical transition. Living during the decline of Zhou authority, he responded not with revolutionary innovation, but with a systematic re-articulation of inherited forms—ritual, education, and moral cultivation—as stabilizing forces capable of sustaining society across generations.

| Structure | Influence on Thought |

|---|---|

| Family + noble lineage | Integrity, perseverance, filial piety |

| Zhou ritual culture | Centrality of li, hierarchy, harmony |

| Study of the Classics | Historical models, moral exemplars |

| Political fragmentation | Focus on ethical leadership and order |

| Master-disciple teaching | Dialogical style, emphasis on self-cultivation |

| Six Arts training | Practical ethics, embodied learning |

| Lens grinding | Precision, geometric thinking, empirical grounding |

Societal Impact

Confucius profoundly shaped East Asian societies by promoting relational ethics (e.g., ren or benevolence, li or ritual propriety) that emphasized harmony through mutual respect and roles, rather than force. His ideas influenced governance in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam for millennia, underpinning imperial examinations, family structures, and social stability.

Neo-Confucianism in the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) integrated his teachings into state ideology, fostering meritocracy and reducing arbitrary rule.

Nuances include its role in promoting education and civility, but also criticisms for reinforcing hierarchies (e.g., patriarchal norms).

In modern contexts, Confucianism inspires “Asian values” debates, balancing collectivism with individual duties, though edge cases show its co-optation for authoritarian control, as in some interpretations during China’s Cultural Revolution.

Methods

Confucius employed dialogic teaching, as recorded in the Analects, using parables, questions, and role modeling to encourage self-reflection. He traveled among states, advising rulers and training disciples, prioritizing practical ethics over abstract metaphysics.

Setbacks

Rejected by many rulers in his lifetime, he faced exile and unemployment, wandering for years without securing a high position. Posthumously, his ideas were suppressed during the Qin Dynasty’s book burnings (213 BCE), only to resurge later.

Annus Mirabilis

Unlike scientists, Confucius lacked a single “miracle year,” but c. 500 BCE marks a peak when he consolidated teachings after returning to Lu, compiling texts and attracting key disciples. This period catalyzed the spread of Confucianism.

Modern Academic Presentation

In today’s setting, Confucius might deliver a TED-style talk or keynote at the American Philosophical Association, using empirical data from sociology (e.g., studies on relational ethics in business) to argue for self-regulation. He’d cite cross-cultural psychology, presenting via PowerPoint with infographics on ethical networks, emphasizing adaptability to globalization while critiquing Western individualism.

A little over 2100 years pass until another human starts as big of a wave. This one originates in northern Europe.

Baruch Spinoza

(1632–1677)

Overview

QUOTES

Minds, however, are conquered not by arms, but by love and nobility.

The highest activity a human being can attain is learning for understanding, because to understand is to be free.

Nothing in nature is by chance… Something appears to be chance only because of our lack of knowledge.

A free man thinks of death least of all things, and his wisdom is a meditation not of death but of life.

No matter how thin you slice it, there will always be two sides.

EDUCATION

Spinoza’s formal schooling took place in the all‑male Talmud-Torah school, founded in 1638. This school was run by adult male teachers, many of whom had been trained in Roman Catholic schools before fleeing Iberian persecution.

From this environment, Spinoza likely learned:

- Hebrew

- Jewish philosophy, including the work of Moses Maimonides

- Elements of Jewish law and tradition (though the curriculum’s depth in traditional Judaism is unclear)

This early education gave him:

Foundation in linguistics | Rationalist approach to scripture | Exposure to philosophical reasoning (embedded in Jewish intellectual traditions)

STRUCTURAL INFLUENCES

Spinoza’s intellectual development was shaped less by formal schooling and more by the social, religious, and intellectual structures around him.

1. Amsterdam’s Marrano-Jewish Community

This background helps explain his later skepticism toward religious authority and his insistence on freedom of thought.

Spinoza’s formal schooling took place in the all‑male Talmud-Torah school, founded in 1638. This school was run by adult male teachers, many of whom had been trained in Roman Catholic schools before fleeing Iberian persecution.

This environment shaped Spinoza by:

- Exposing him to religious pluralism and the fragility of dogma

- Surrounding him with people who had lived through persecution, secrecy, and identity conflict

- Creating a culture where rational debate and interpretation were necessary for survival

2. Catholic Teachers — Neither Marrano nor Jewish

A hybrid Jewish–Catholic intellectual environment is unusual; and it seeded the analytic precision that later appears in the Ethics.

Because many teachers had Catholic educations, Spinoza indirectly absorbed:

- Scholastic methods

- Latinized philosophical categories

- A tradition of rigorous logical argumentation

3. Heterodox Communities

By his early 20s, Spinoza was already involved in teaching and discussing ideas that challenged biblical literalism.

- He owned La Peyrère’s Prae-Adamitae, a radical text questioning biblical history

- He participated in Sabbath school discussions that raised doubts about scripture

- He was investigated for potential heresy

This early exposure to critical biblical scholarship shaped his later methods.

4. Collegiants, Quakers, and Radical Protestant Circles

Spinoza’s engagement in fringe societies after his excommunication, helped shape his trademark political and theological radicalism.

These circles include:

- Collegiants — anti-dogmatic, creedless Christians

- Quakers — who rejected ritual and emphasized inner light

- Samuel Fisher, a Quaker scholar of Hebrew

- Pieter Balling, a Collegiant philosopher

Ideas they reinforced:

Anti-authoritarian religious views | Individual reason | Skepticism toward ritual and tradition | Unmediated access to truth

5. Scientific and Philosophical Correspondence

Spinoza’s move to Rijnsburg and The Hague brought him into contact with key figures who shaped his commitment to determinism, naturalistic explanations, the rejection of miracles, and a geometric method of proof.

Because many teachers had Catholic educations, Spinoza indirectly absorbed:

- Henry Oldenburg, future secretary of the Royal Society

- Robert Boyle, a founder of modern chemistry

- Later, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

These relationships exposed him to mechanistic physics, empirical science, and rationalist metaphysics.

6. Lens Grinding

Grinding lenses, a hands-on scientific craft, influenced the structure of his meticulous nature, geometric and grounded in natural law.

Though not formal education, his work grinding lenses:

- Immersed him in optics

- Connected him to scientific networks

- Reinforced a worldview grounded in precision, mechanics, and clarity

STRUCTURAL ECOLOGY

From this environment, Spinoza likely learned:

| Structure | Influence on Thought |

|---|---|

| Talmud-Torah school | Hebrew, Jewish philosophy, rational interpretation |

| Marrano-Jewish community | Skepticism of authority, pluralism, identity complexity |

| Teachers with Catholic training | Scholastic logic, Latinized categories |

| Heterodox texts & debates | Critical biblical analysis, naturalism |

| Collegiants & Quakers | Anti-dogmatism, freedom of thought |

| Scientific networks | Mechanistic worldview, determinism |

| Lens grinding | Precision, geometric thinking, empirical grounding |

Spinoza’s mind was shaped by borderlands — between religions, cultures, languages, and intellectual traditions. That liminal position is exactly what made his philosophy so original.

Societal Impact

Spinoza’s pantheism —equating God with nature’s structure— demystified divinity, shifting agency to humans via reason and ethics.

This influenced the Enlightenment, secularism, and modern democracy, inspiring thinkers like Locke and Voltaire. Examples include its role in separating church and state, fostering tolerance (e.g., in the Dutch Republic).

Nuances: His determinism balanced free will with necessity, promoting emotional self-mastery.

Implications: In society, it undercut religious authoritarianism, but edge cases involve misapplications, like equating it with atheism, leading to cultural backlash.

Methods

Spinoza used the “geometric method” in Ethics (1677), proving propositions axiomatically like Euclid, blending rational deduction with metaphysical insight to reframe reality as a unified substance.

Other methods include treating scripture as a historical document, using linguistic and contextual analysis, and rejecting supernatural explanations.

Setbacks

Excommunicated from the Jewish community in 1656 for heresy, he lived in isolation, grinding lenses for income. His works were banned, published anonymously or posthumously, delaying recognition.

Annus Mirabilis

1670, when he published the Theological-Political Treatise, boldly critiquing scripture and advocating freedom of thought, sparking widespread debate despite censorship.

Modern Academic Presentation

Spinoza could appear at a Society for Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy conference, using formal logic and neuroscience slides (e.g., linking affects to brain scans) to defend pantheism. He’d engage Q&A analytically, publishing in open-access journals to mirror his emphasis on accessible reason.

Fifty-four years after the igniting the match of enlightenment, our next giant, Kant, is born.

Immanuel Kant

(1724–1804)

QUOTES

Science is organized knowledge. Wisdom is organized life.

Do the right thing because it is right.

Experience without theory is blind, but theory without experience is mere intellectual play.

Happiness is not an abstract idea; it is a condition of acting according to reason.

The only thing permanent is change.

EDUCATION

Kant’s education was far more formal than Spinoza’s, but it was shaped by similarly powerful cultural and intellectual structures. His development moved through three major phases: Pietist schooling, university training, and self-directed synthesis during his long period as an unsalaried lecturer.

1. Pietist schooling (Ages 8–15)

Kant attended the Collegium Fridericianum, a strict Pietist school emphasizing biblical study, moral discipline, intense introspection, and religious emotion and conversion.

Kant reacted strongly against this environment, seeking refuge in Latin classics, which were central to the curriculum.

This early tension shaped him by:

- Instilling a lifelong suspicion of emotionalism

- Pushing him toward reason, autonomy, and self-legislation

- Giving him a rigorous linguistic and classical foundation

Where Spinoza reacted against religious dogma by turning toward rational critique, Kant reacted against Pietist emotionalism by turning toward autonomy and the sovereignty of reason.

2. University of Königsberg (The Albertina)

In the Zhou world, “education” meant mastering the Six Arts (六艺, Liù Yì), an educational curriculum that aligned body, emotion, intellect, and ethics —a whole-person education.

These arts echo through later East Asian culture—martial arts, music pedagogy, calligraphy, even governance theory. Strip away the bronze vessels and chariots, and the underlying question still hums: What should a complete education actually cultivate?

| Art | Character | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ritual | 礼, Lǐ | Ritual was more than empty ceremony—ritual was social physics. It trained people to move through hierarchy, grief, joy, and power without tearing the fabric of the group. | Confucius saw lǐ as the external form of inner virtue. |

| Music | 乐, Yuè | Music shaped emotion and character. Proper music cultivated harmony; chaotic music signaled social decay. | Confucius famously judged governments by their music before their laws. Sound as moral technology. |

| Archery | 射, Shè | This wasn’t just about hitting a target. Archery trained posture, breath, focus, and humility. | In ritual archery contests, moral composure mattered more than accuracy—miss the target calmly, and you still passed. |

| Charioteering | 御, Yù | Driving a chariot required coordination, awareness, and trust. Symbolically, it trained leaders to “hold the reins” of themselves before attempting to guide others. | Power without self-control was considered dangerous. |

| Calligraphy | 书, Shū | Writing wasn’t neutral transcription. Calligraphy revealed the mind through the body. | Stroke order, pressure, and rhythm were read as windows into character—thought made visible. |

| Mathematics | 数, Shù | Math grounded philosophy in reality: land measurement, astronomy, calendars, logistics. | Pattern recognition in numbers mirrored the larger patterns of Heaven and Earth. |

Confucius’s Perspective

As a young man, Confucius received a broad classical education associated with the remnants of Zhou aristocratic culture, studying ritual, music, history, and administrative practices. Although not born into the ruling elite, he sought mastery of the cultural forms that had once structured political legitimacy. This outsider-insider position—trained in elite norms but excluded from hereditary power—became a defining feature of his intellectual trajectory.

3. Private Tutor to University Lecturer

After university, Kant spent six years as a private tutor, then returned to the university as an unsalaried lecturer (1755–1770). He taught logic, metaphysics, ethics, mathematics, physics, and physical geography.

He relied on Wolffian textbooks, but used them loosely, integrating ideas from British sentimentalists (Hume, Hutcheson), Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Newtonian science.

- The Book of Songs

- The Book of Documents

- The Book of Rites

- The Spring and Autumn Annals

- The Book of Changes

This period is similar to Spinoza’s years of lens-grinding and correspondence: a long, quiet period of self-formation outside formal institutional power.

STRUCTURAL INFLUENCES

1. Pietist Culture of Königsberg

Spinoza rejected religious authority to defend freedom of thought; Kant rejected religious emotionalism to defend moral autonomy.

Pietism emphasized inner moral life, discipline, personal responsibility, and suspicion of external authority. Kant rejected Pietist emotionalism but absorbed its more seriousness and emphasis on duty.

This shaped

- His belief in autonomy

- His view that morality is grounded in reason, not emotion

- His insistence on self-legislation

2. Leibniz–Wolff Rationalism vs. British Empiricism

Where Spinoza unified rationalism and biblical criticism, Kant unified rationalism and empiricism into a new philosophical method.

Exposure to British empiricism (through Locke, Hume, and Hutcheson), created an internal tension that shaped his entire project. This pushed him toward:

- A synthesis of rationalism and empiricism

- A critique of both traditions

- The development of transcendental philosophy

3. Newtonian Science

Kant embraced a deterministic, law-governed universe perspective. His work rebuilt the foundations of determinism inside the structures of the mind.

Through Knutzen, Kant absorbed Newton’s physics early. Newton’s influence appears in:

- His early scientific works

- His belief in universal laws

- His later attempt to ground science in a priori principles

This shaped his intellectual process by:

- Making him seek necessary structures behind empirical phenomena

- Reinforcing his belief in law-governed nature

- Driving his “Copernican revolution” structures behind empirical phenomena

4. The Crisis of the Enlightenment

Where Spinoza defended freedom of thought against religious authority, Kant defended reason itself against skepticism and dogmatism.

Kant lived at a moment when:

- Science threatened traditional morality

- Skepticism threatened metaphysics

- Reason itself was under suspicion

This crisis shaped his project:

- To secure science

- To secure morality

- To secure freedom

- To reconcile them through autonomy

5. Academic Life and Public Debate

Spinoza wrote for a small circle; Kant wrote for a public sphere.

Kant’s world included:

- Prize competitions

- Reviews

- Public controversies (e.g., the pantheism debate)

- A growing philosophical community

zThis shaped his intellectual process by:

- Forcing clarity

- Encouraging systematic presentation

- Pushing him to refine his ideas in response to criticism

STRUCTURAL ECOLOGY

Kant’s education was a layered progression from Pietist discipline to university rationalism, to self-directed synthesis. His intellectual process was shaped by:

| Structure | Influence on Thought |

|---|---|

| Pietist schooling | Moral seriousness, autonomy, rejection of emotionalism |

| University rationalism + empiricism | Drive to synthesize competing systems |

| Newtonian science | Law-governed nature, a priori structure |

| Enlightenment crisis | Need to secure science, morality, and freedom |

| Master-disciple teaching | Dialogical style, emphasis on self-cultivation |

| Academic culture | Systematic method, public reasoning |

| Long period as lecturer | Breadth, independence, synthesis |

Kant, like Spinoza, was shaped by a tension-filled intellectual ecosystem — but where Spinoza turned toward naturalism and biblical criticism, Kant turned toward autonomy, transcendental structure, and the limits of reason.

Outcome: Philosophy that secures both science and morality by locating necessary conditions in the mind.

Societal Impact

Kant’s framework for self-governance via the categorical imperative (“act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law”) revolutionized ethics, influencing human rights, international law, and liberalism. It shaped the UN Declaration of Human Rights and modern deontology.

Examples: His “perpetual peace” essay informed the League of Nations.

Nuances: Imperfectly, as noted, it struggled with cultural relativism.

Implications: Promoted autonomy in education and politics, but edge cases include rigid applications ignoring consequences, as in some bioethics debates.

Methods

Critical philosophy, synthesizing empiricism and rationalism through a priori categories, as in his Critiques (1781–1790), using transcendental arguments to explore mind’s role in structuring experience.

Setbacks

Health issues (hypochondria) and censorship (e.g., Frederick William II banned his religious writings in 1794) limited output. Early works were overlooked, delaying fame until his 50s.

Annus Mirabilis

1781, publishing Critique of Pure Reason, a watershed redefining epistemology and metaphysics, followed by rapid sequels.

Modern Academic Presentation

Kant might keynote at the Kant Society, employing VR simulations of moral dilemmas or AI ethics panels to illustrate self-governance. He’d use data from behavioral economics, submitting to peer-reviewed journals with rigorous appendices.

After his death in 1804, eighty-five years pass before our next giant, Ludwig Wittgenstein, is born.

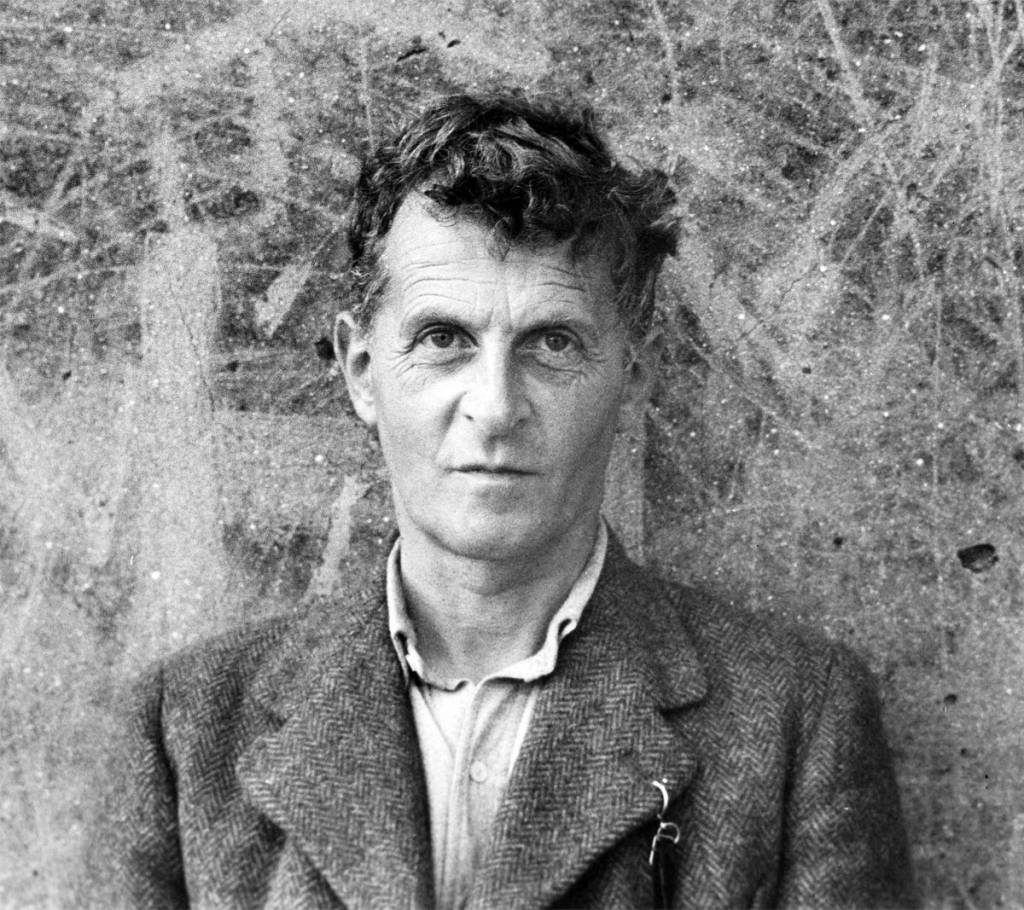

Ludwig Wittgenstein

(1889–1951)

QUOTES

We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have still not been touched at all.

There can never be surprises in logic.

The problems are solved, not by giving new information, but by arranging what we have known since long.

The human body is the best picture of the human soul.

Knowledge is in the end based on acknowledgement.

EDUCATION

His education began in engineering, continued in analytic logic under Frege and Russell, and matured through solitary reflection and teaching.

Where Kant grew up in a modest Pietist household and Spinoza in a Marrano‑Jewish merchant community, Wittgenstein grew up in a cosmopolitan, aristocratic, artistic world.

1. Cultural World: Fin‑de‑Siècle Vienna

Wittgenstein was born into one of the wealthiest industrial families in Vienna. This placed him at the center of a cultural environment unlike any philosopher we’ve covered so far:

Kant reacted strongly against this environment, seeking refuge in Latin classics, which were central to the curriculum.

This early tension shaped him by:

- Vienna was a hub of music, architecture, psychoanalysis, and scientific modernism.

- His family home was a gathering place for artists and intellectuals.

- The Wittgensteins were patrons of the arts, deeply embedded in elite Viennese culture.

Where Kant grew up in a modest Pietist household and Spinoza in a Marrano‑Jewish merchant community, Wittgenstein grew up in a cosmopolitan, aristocratic, artistic world.

2. Early Life & Family

Wittgenstein was born April 26, 1889, in Vienna, Austria.

His family background shaped him profoundly:

- His father, Karl Wittgenstein, was a steel magnate, one of the richest men in Europe.

- His mother, Leopoldine, cultivated a home steeped in music and culture.

- Several of his siblings were gifted artists or musicians; some struggled with mental illness.

This environment produced a perfectionistic, intense personality with a deep connection to music (which later shaped his sense of “grammar” and “harmony” in language). It also produced a lifelong struggle with existential seriousness.

Compared to Kant’s humble upbringing and Confucius’s early poverty, Wittgenstein’s childhood was one of wealth, pressure, and cultural refinement.

Confucius’s Perspective

As a young man, Confucius received a broad classical education associated with the remnants of Zhou aristocratic culture, studying ritual, music, history, and administrative practices. Although not born into the ruling elite, he sought mastery of the cultural forms that had once structured political legitimacy. This outsider-insider position—trained in elite norms but excluded from hereditary power—became a defining feature of his intellectual trajectory.

3. Engineering Studies in Manchester (1908)

At age 19, Wittgenstein left Vienna for England to study aeronautical engineering at Manchester University. This phase shaped him by:

- Training him in mathematical precision

- Exposing him to the technical limits of explanation

- Awakening his interest in the foundations of mathematics

This period is similar to Spinoza’s years of lens-grinding (precision + mechanics) and Kant’s Newtonian scientific training (structure + necessity).

But Wittgenstein’s engineering background made him uniquely allergic to philosophical vagueness.

4. Turning Toward Philosophy: Frege → Cambridge

While studying engineering, Wittgenstein became obsessed with the philosophy of pure mathematics. At the age of 22, this led him to seek out Gottlob Frege, who immediately recognized his talent and advised him to study with Bertrand Russell at Cambridge in 1911. This apprenticeship shaped him by:

- Immersing him in the most advanced logic of the time

- Giving him a model of philosophy as analysis and clarity

- Forming intense intellectual relationships (Russell, Moore, Keynes)

This is the opposite of Confucius’s ritual‑based education and Kant’s structured university training — Wittgenstein’s philosophical education was personal, intense, and mentor‑driven.

STRUCTURAL INFLUENCES

1. Austro-Hungarian Intellectual Culture

This gave him a sensitivity to form, structure, and limits — themes that dominate both the Tractatus and the Investigations.

Vienna’s intellectual world shaped him with music, logic, architecture, psychoanalysis, and scientific modernism.

2. Foundational Crisis in Mathematics

Like Kant responding to the crisis of reason, Wittgenstein responded to the crisis in the foundations of mathematics.

This shaped him by:

- Making him suspicious of abstraction

- Driving him toward logical atomism (early)

- Later pushing him toward ordinary language as the true ground of meaning

3. Cambridge Philosophical Community

Wittgenstein ultimately turned against academic philosophy itself.

His interactions with Russell, Moore, Keynes, and later students shaped him by:

- Giving him a model of philosophy as argument and analysis

- Later pushing him to reject that model in favor of therapy and description

This is similar to:

- Spinoza’s correspondence, which sharpened his ideas

- Confucius’s disciples, who shaped his teaching style

- Kant’s academic environment, which forced systematic clarity

4. Solitude, Exile, and Personal Crisis

Like Confucius, who also saw wisdom in ordinary life, Wittgenstein repeatedly left academia.

He worked as:

- A schoolteacher

- A gardener

- An architect

- A hermit-like thinker

These experiences shaped him by:

- Grounding his philosophy in everyday life

- Reinforcing his suspicion of theory

- Making him attentive to forms of life and practices

5. Rejection of His Own Earlier Work

Wittgenstein repudiated the Tractatus and built a new philosophy from scratch.

No philosopher we’ve covered undergoes a transformation as radical as Wittgenstein’s.

- Spinoza refined his ideas

- Confucius deepened a tradition

- Kant revolutionized but did not reject his earlier work

How this affected his psyche:

- Making self-critique central

- Treating philosophy as a process, not a system

- Emphasizing flexibility, context, and use

STRUCTURAL ECOLOGY

| Structure | Influence on Thought |

|---|---|

| Family | Extremely wealthy Viennese industrialists |

| Cambridge & Russell | Logic, analysis, philosophical rigor |

| Isolation and war | Mysticism, limits of language, ethical silence |

| Enlightenment crisis | Need to secure science, morality, and freedom |

| Vienna Circle | Reaction against dogmatism, shift to ordinary language |

| Teaching & dialogue | Language-games, forms of life, therapeutic method |

| Personal crises | Anti-theory stance, emphasis on practice |

Of the great thinkers we’ve covered, Wittgenstein is the most existential, self-critical, and methodologically radical— and comparing him to Spinoza, Confucius, and Kant reveals just how differently a philosophical mind can be formed.

His method transformed philosophy as clarification of language‑use and attention to forms of life rather than system building.

Societal Impact

Wittgenstein’s view that philosophical problems stem from linguistic misuse liberated thought from artificial constraints, influencing analytic philosophy, linguistics, and AI. It affected education (e.g., critical thinking curricula) and therapy (e.g., resolving conceptual confusions).

Examples: Language games in Philosophical Investigations (1953) informed postmodernism and cognitive science.

Nuances: Shifted from logical positivism to ordinary language.

Implications: Reduced dogmatic debates, but edge cases include over-relativism, as in some cultural studies misusing “private language” arguments.

Methods

Early logical atomism (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 1921) used propositions to mirror reality; later, descriptive analysis of language use in everyday contexts.

Setbacks

WWI trauma, academic rejections (e.g., Cambridge disputes), and personal isolation; he abandoned philosophy temporarily for teaching and architecture.

Annus Mirabilis

1929, his transitional year returning to Cambridge, rethinking earlier ideas and laying groundwork for later work.

Modern Academic Presentation

In a Wittgenstein Society webinar, he’d use interactive polls and memes to demonstrate language “misfiring,” collaborating with linguists via Zoom. Publications would be concise, aphoristic papers in digital formats.

Hannah Arendt

(1906–1975)

QUOTES

Evil thrives on apathy and cannot exist without it.

The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.

Politically, the weakness of the argument has always been that those who choose the lesser evil forget very quickly that they chose evil.

We are free to change the world and start something new in it.

Storytelling reveals meaning without committing the error of defining it.

EDUCATION

Education under Heidegger, Husserl, and Jaspers combined existential phenomenology, descriptive rigor, and dialogical concern for politics.

Arendt’s education was deeply academic, rigorously philosophical, and profoundly shaped by the German university system of the early 20th century. Her formation moved through three major phases: Heidegger, Husserl, and Jaspers — each leaving a distinct imprint on her intellectual style.

1. Marburg University (1924)

After finishing high school, Arendt went to Marburg University specifically to study with Martin Heidegger, philosopher of hermeneutics and existentialism.

Kant reacted strongly against this environment, seeking refuge in Latin classics, which were central to the curriculum.

This early tension shaped him by:

- Immersing her in phenomenology, especially Heidegger’s focus on being, existence, and authenticity.

- Introducing her to philosophy as a question of lived experience, not abstract system-building.

- Exposing her to Heidegger’s method of deconstructing tradition to recover original meanings — a method she later adapted in her own work.

Arendt’s education was deeply academic, rigorously philosophical, and profoundly shaped by the German university system of the early 20th century. Her formation moved through three major phases: Heidegger, Husserl, and Jaspers — each leaving a distinct imprint on her intellectual style

- Wittgenstein’s apprenticeship with Russell (intense, personal, transformative)

- Kant’s early formation under Knutzen, who shaped his intellectual direction

- Spinoza’s early exposure to heterodox thinkers, which redirected his philosophical path

2. Freiburg University (1925)

After a year at Marburg, Arendt moved to Freiburg to attend the lectures of Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology.

This shaped her by:

- Giving her exposure to rigorous descriptive analysis of consciousness

- Reinforcing the idea that philosophy begins with careful attention to experience

- Providing a counterbalance to Heidegger’s existential approach

Husserl’s influence helped her develop the clarity and precision that later appear in The Human Condition.

3. Heidelberg University (1926)

In 1926, Arendt moved to Heidelberg to study with Karl Jaspers, with whom she formed a lifelong intellectual and personal friendship.

She completed her dissertation, Der Liebesbegriff bei Augustin (The Concept of Love in Augustine), under his supervision in 1929.

Jaspers shaped her by:

- Emphasizing communication, freedom, and the public sphere

- Encouraging her interest in political existence, not just metaphysics

- Modeling a philosophy grounded in dialogue, plurality, and human dignity

STRUCTURAL INFLUENCES

1. German-Jewish Cultural Background

Arendt’s experience was marked by the rise of antisemitism and the collapse of European political structures.

Arendt was born into a German-Jewish family in 1906. This shaped her by:

- Giving her early exposure to Jewish intellectual traditions

- Positioning her at the intersection of assimilation, identity, and political vulnerability

- Making her acutely aware of the fragility of rights and citizenship

This background parallels:

- Spinoza’s Marrano-Jewish context, which shaped his suspicion of dogma

- Kant’s Pietist upbringing, which shaped his moral seriousness

2. Exile and Totalitarianism

This is unlike any of the other thinkers we’ve covered — her philosophy is born directly from political catastrophe.

Arendt was forced to flee Germany in 1933 due to Hitler’s rise to power. She lived in Paris for eight years, working with Jewish refugee organizations, before fleeing again to the United States in 1941.

This shaped her by:

- Making statelessness, refugeehood, and the loss of rights central to her political thought

- Giving her firsthand experience of totalitarianism, which became the subject of her first major book

- Reinforcing her belief that political philosophy must confront real historical events, not abstract systems

3. Phenomenology and Existentialism (Heidegger, Husserl, Jaspers)

Arendt’s three major teachers shaped her method.

| Heideger | deconstruction of tradition, focus on existence |

| Husserl | descriptive rigor, attention to experience |

| Jaspers | communication, freedom, political responsibility |

These influences shaped her thought patterns by:

- Making her suspicious of abstract system-building (unlike Kant)

- Grounding her work in experience, action, and plurality

- Encouraging her to read the past through fragments, not grand narratives

4. Journalism, Public Debate, and the Partisan Review Circle

Like Confucius, who also saw wisdom in ordinary life, Wittgenstein repeatedly left academia.

After arriving in New York, Arendt became part of a vibrant intellectual circle around the Partisan Review.

This shaped her by:

- Reinforcing her belief in public discourse and political plurality

- Giving her a platform to develop her ideas in dialogue with others

- Encouraging her to write in a style accessible to both scholars and the public

This is similar to Kant’s engagement with the public sphere and Wittgenstein’s later dialogical teaching style. But Arendt’s public engagement was explicitly political and journalistic.

5. The Collapse of Tradition and the Need for New Categories

Arendt believed that totalitarianism had broken the continuity of Western tradition, making old categories unusable (source).

This shaped her by:

- Pushing her to develop new conceptual frameworks

- Leading her to reinterpret the Greek polis as a model for political action

- Making her skeptical of inherited philosophical systems

This is a structural parallel to:

- Wittgenstein’s rejection of his own earlier philosophy

- Kant’s critical project, which rebuilt philosophy from new foundations

But Arendt’s reconstruction is explicitly political, not epistemological or linguistic.

STRUCTURAL ECOLOGY

| Structure | Influence on Thought |

|---|---|

| German-Jewish upbringing | Identity, vulnerability, rights |

| Heidegger (Marburg) | Existential analysis, deconstruction |

| Husserl (Freiburg) | Phenomenological rigor |

| Jaspers (Heidelberg) | Communication, political responsibility |

| Exile & totalitarianism | Focus on statelessness, evil, political action |

| Partisan Review circle | Public discourse, political writing |

| Breakdown of tradition | Need for new categories, fragmentary method |

This structural combination produced a political theory grounded in action, plurality, natality, and the space of appearance; a method that treats events and narratives as primary data for political concepts.

Societal Impact

Arendt’s warning about thoughtless conformity causing systemic collapse (e.g., “banality of evil” in Eichmann in Jerusalem, 1963) reshaped political theory, influencing human rights activism and critiques of bureaucracy. It informed post-WWII trials and modern discussions on populism.

Examples: The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) analyzed fascism and communism.

Nuances: Emphasized active thinking (vita activa).

Implications: Encouraged civic engagement, but edge cases involve accusations of victim-blaming in Holocaust analyses.

Methods

Phenomenological and historical analysis, drawing on archives and observations to dissect power structures.

Setbacks

Fled Nazi Germany in 1933, statelessness until 1951; faced backlash for Eichmann coverage, including personal attacks.

Annus Mirabilis

1951, publishing The Origins of Totalitarianism, a landmark synthesizing her exile experiences.

Modern Academic Presentation

At a Political Science Association panel, Arendt might use case studies from social media echo chambers, presenting with multimedia (e.g., videos of protests). She’d favor interdisciplinary journals, engaging debates on platforms like Academia.edu.

Ties Binding Their Main Claims

The core tie is the promotion of individual agency and critical self-regulation against external or systemic constraints. Confucius and Kant focus on ethical frameworks for autonomy; Spinoza reframes metaphysics to empower reason; Wittgenstein liberates thought from linguistic traps; Arendt warns of collapse without independent thinking. Together, they form a continuum from ancient ethics to modern politics, emphasizing that true societal stability arises from internalized, thoughtful governance rather than coercion. Nuances: This counters divine/ruler authority (Confucius, Spinoza) and highlights language/thought’s role in freedom (Wittgenstein, Arendt). Implications: In edge cases, like AI ethics, their ideas warn against algorithmic “obedience” supplanting human judgment.

Comparison Across Structural Categories

| Philosopher | Education | Cultural Background | Key Mentors/Institutions | Formative crises / experiences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confucius | Family-based, apprenticeship in the Six Arts; mastery of ritual and classics | Zhou aristocratic tradition; ritual-centered society | Local ritual specialists; transmission of the early Zhou classics | Political fragmentation of the Spring and Autumn period |

| Spinoza | Talmud‑Torah schooling; self‑study and correspondence; no university degree | Marrano‑Jewish community in Amsterdam; multilingual merchant milieu | Talmud‑Torah teachers; heterodox Jewish and Protestant circles; scientific correspondents | Excommunication, exile from Jewish community; engagement with scientific networks |

| Kant | Classical schooling; University of Königsberg (Albertina); long period as unsalaried lecturer | Pietist provincial Prussia; Enlightenment scientific culture | Martin Knutzen; Wolffian university curriculum; Newtonian science | Enlightenment crises: skepticism, rise of modern science, need to secure morality and knowledge |

| Wittgenstein | Engineering training (Manchester); apprenticeship with Frege and Russell; solitary self‑study | Fin‑de‑siècle Viennese elite culture; musical and artistic household | Gottlob Frege; Bertrand Russell; Cambridge circle | War service, long periods of exile and manual work; radical self‑revisions of his own philosophy |

| Hannah Arendt | German university formation across Marburg, Freiburg, Heidelberg; doctoral dissertation | German‑Jewish upbringing; cosmopolitan German intellectual life | Martin Heidegger; Edmund Husserl; Karl Jaspers; Partisan Review circle in New York | Forced exile from Nazi Germany; work with refugees; witnessing totalitarianism and Eichmann trial |

Overall Impact on Human Society

Their collective influence fostered shifts toward secular, democratic, and reflective societies, underpinning Enlightenment values, human rights, and critical theory. Impacts include reduced religious wars (Spinoza), merit-based systems (Confucius), moral universalism (Kant), clearer discourse (Wittgenstein), and vigilance against authoritarianism (Arendt). However, setbacks like misappropriations (e.g., Confucianism for conformity) highlight nuances. In 2026, amid AI and global crises, their emphasis on agency remains vital, influencing policies on education and governance.

Recommended Academic Journal

Given the interdisciplinary blend of ethics, metaphysics, language, and systemic critique—with ties to consciousness and mind—the Journal of Consciousness Studies would aptly host their insights, as it bridges philosophy, psychology, and society, allowing speculative yet rigorous discussions on agency and thought. Alternatives like Ethics or Philosophy & Social Criticism could fit, but JCS’s focus on mindful autonomy best captures the essence.

Quick Takeaways

Education is ecological

Family, institutions, mentors, crafts, and crises combine to produce a philosopher’s method.

Tension breeds method

Each thinker’s distinctive method answers a specific tension in their formation (ritual vs. collapse; scripture vs. science; Pietism vs. Enlightenment; engineering vs. philosophy; phenomenology vs. totalitarian catastrophe).

Comparative insight

Spinoza and Kant both synthesize scientific and philosophical inputs but in different directions — Spinoza toward metaphysical naturalism, Kant toward conditions of possibility for knowledge and morality. Wittgenstein and Arendt share an anti‑system impulse but differ in focus — language and therapy versus political action and historical judgment.

Leave a comment